Onions and the amazing truth behind a French stereotype

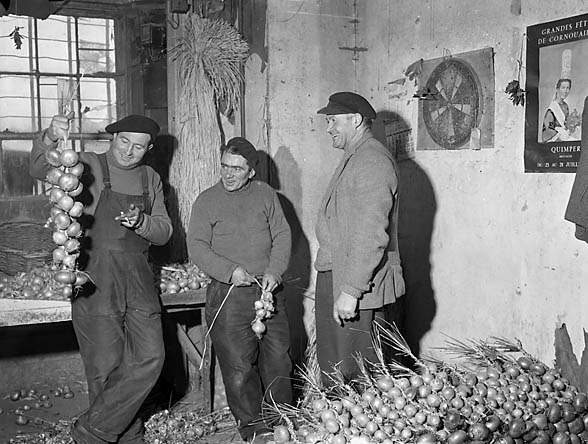

Picture the most outrageously caricature version of a French man you can. If you’re anything like me, you’ll have imagined something similar to the image that accompanies this post: a moustachioed gent in a striped jumper and beret. And, if you’re British, there’s a good chance that your imagination will have added a string of onions around his neck.

An onion necklace – where with the what now? Everyone’s on board with the stripy top-beret stereotype but it seems to be a British quirk to associate the French with onion accessories. Now I can personally confirm that, from the Claire’s Accessories in my local shopping centre to oh-so-robbable Cartier showrooms of Paris, I have never seen an onion necklace on sale. Yes, I’m so sorry to disappoint; what can I say, reality is a cup of cold sick.

So where does this idea come from? Did the French ever wear onions necklaces, you know, in Ye Olde Times? Perhaps they were centuries ahead of Lady Gaga’s meat dress in making fashion statements with food. Or prudent in personal defence against vampires. Or even partial to an easy onion snacking opportunity.

It turns out to be none of those things. I KNOW!

Weirder still is the fact that there is a historical basis for this British perception of French people. So settle down comfortably with a bowl of French onion soup because we are going IN.

Our story begins in early nineteenth century Brittany with an onion farmer named Henri Ollivier. This adventurous chap decided, instead facing an arduous trip to Paris via the poorly maintained roads or embryonic rail system to sell his onions, that he would hop across the Channel to try his luck in Blighty instead. He made the right call. So profitable was his onion-selling escapade that it inspired hundreds of others to follow suit. By the 1920s, 1,400 onion sellers from Brittany were making the annual trip to sell their wares in the UK, as far north as Scotland. Many of them headed to Wales where the Breton-speaking sellers found it easier to communicate with the similarly Celtic-tongued Welsh speakers.

In the 1920s, at the peak of trade, these Bretons sold 9,000 tonnes of onions. To put it into perspective, that amount of onions weighs the same as nine-tenths of the Eiffel Tower, or 360,000 French poodles.

That’s a lot of onions.

It’s fair to say that these onions sellers didn’t go unnoticed in Britain. Indeed, so familiar a sight were these Franco trader-invaders that they earned their own nickname, Onion Johnnies. These Onion Johnnies would go door-to-door selling onions, transporting their goods on bikes. Being from Brittany, they often wore the traditional Breton jumper – the stripy top of French stereotype fame. At the time, this was the only contact most British people would have had with French people, so it is easy to see how the character of the Onion Johnny became asscociated with the French in general.

But what of the onions? We’ve grown onions in Britain for hundred of years. What was so special about Johnny Foreign onions? Well, as Marks and Spencers so memorably said, they weren’t just any onions, they were Roscoff onions. This is a variety of onion grown only in the Finistère region of Brittany and prized for their unique, sweet flavour and pale pink colour. (Pink onions! How delightful!) Not only that, they were known for their long shelf life. A sound and delicious investment indeed.

This being a story about onions, however, it’s natural that there should be some tears. In 1905, 125 people, including seventy onion sellers, died returning from England when their ship, the SS Hilda, sank in bad weather off St Malo. At the hundredth anniversay of the tragedy, a religious service was conducted at sea, then divers attached a string of onions to the shipwreck in memory of those who lost their lives.

The heyday of the Onion Johnny wasn’t to last. The Great Depression of the 1930s, followed by World War II, then import restrictions reduced trade dramatically until there were only twenty Onion Johnnies by the end of the twentieth century. Once a familiar sight on the streets of Britain, now we are left with only this curious image of a Frenchman carrying onions on a bike, without context.

But what of those onion necklaces? These seem to be a fanciful British invention, an imaginative extension of the strings of onions carried by the Onion Johnnies. Aside from caricatures and fancy dress costumes, the only evidence I can find of an onion necklace on a French person is the (presumably) ironic wearing of one by the actress/model and daughter-of-famous-parents Lily-Rose Depp.

That’s not the only legacy of the Onion Johnnies, thankfully. A more lasting and fitting tribute to the adventure and industry of these men can be seen in the creation of Brittany Ferries. Set up in the 1970s by a group of Breton farmers, these ferries follow in the footsteps of Henri Ollivier by opening up trade routes by sea with neighbouring Britain. Every year over 2.5 million people travel between Britain and France using the service, and, in so doing, learning about French or British people and culture, dismantling stereotypes with every visit.